Tokens Ownership

Everything you need to know about token ownership on blockchains

Token Ownership: A Short History and Why It Matters

Token ownership means recording who controls a digital asset on a public ledger, enforced by cryptography and consensus rather than by legal registries alone. It unlocks portable, programmable, and verifiable property rights for anything that can be represented in bits.

From Scarcity to Programmability

- Bitcoin (2009) solved digital scarcity and established provable, bearer‑style ownership “by code.”

- Ethereum (2015) generalized ownership with smart contracts, enabling tokens: programmable representations of value, access, or rights. The 2014–2018 wave of token sales showed how ownership could be distributed globally without intermediaries—sometimes as utility access, sometimes (mistakenly) as implied equity. The lesson: tokens coordinate, but value capture must be designed, not assumed.

What “Ownership” Means On‑Chain

On blockchains, ownership is:

- Verifiable: anyone can audit balances and provenance.

- Portable: assets move across apps and wallets with private keys.

- Programmable: rights can encode governance, access, royalties, staking, or fee distribution.

- Composable: tokens integrate with DeFi, marketplaces, and tooling by common standards.

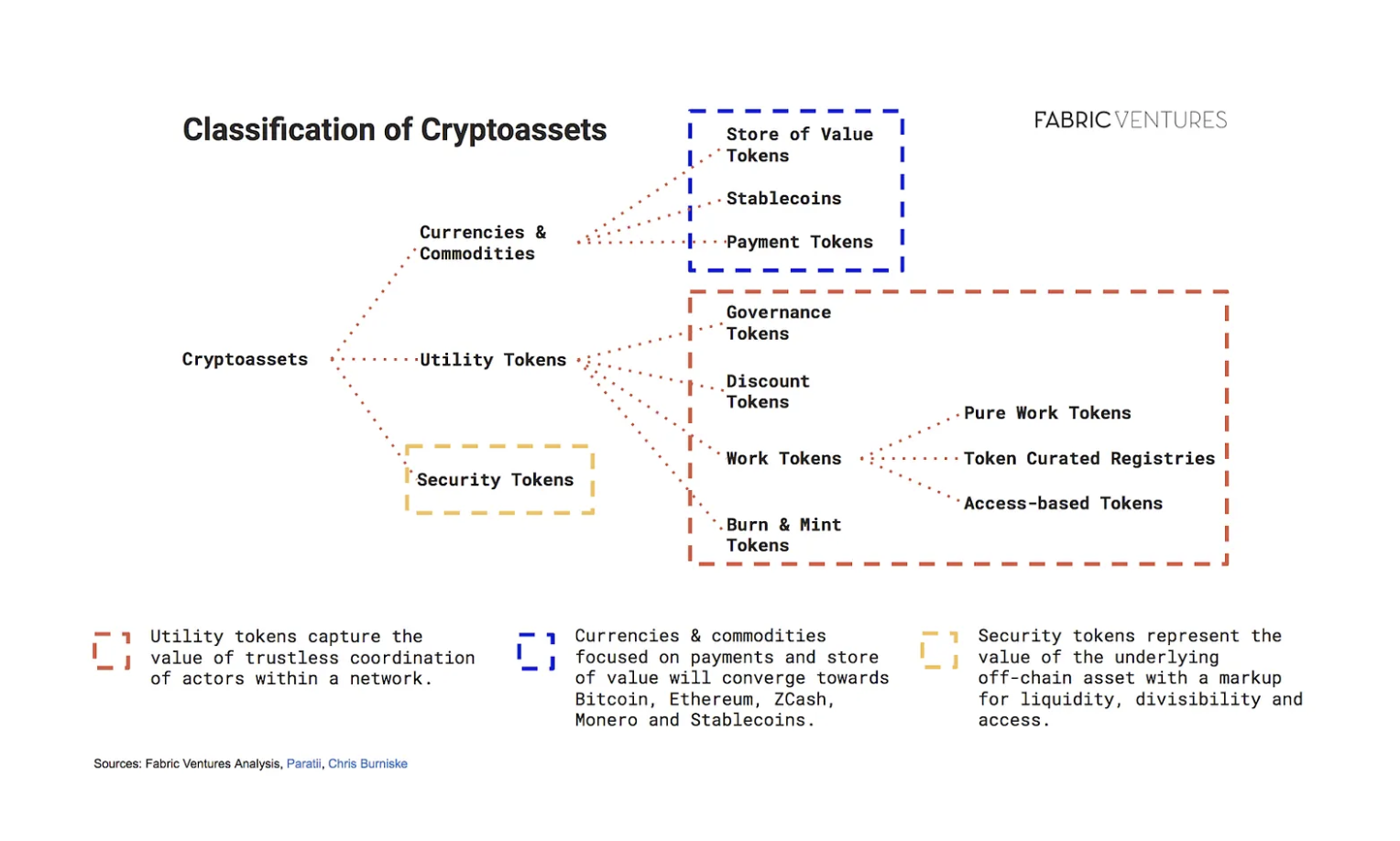

Token Classes at a Glance

At a high level:

- Fungible tokens (e.g., ERC‑20) track interchangeable units (balances, payments, governance power).

- Non‑fungible tokens (e.g., ERC‑721) track unique items and their provenance (collectibles, credentials, rights).

- Hybrids and multi‑tokens (e.g., ERC‑1155) combine both models for efficient gaming/commerce flows.

Why Tokenized Ownership Works

Tokens drastically reduce friction to distribute and align ownership. Like equity, they can motivate long‑term contribution; unlike equity, they are programmable (e.g., automatic reward streams, on‑chain voting) and readily tradable. But not every token confers the same rights: designs differ in value capture (fee burns, staking rewards, access discounts), transferability, and governance—and must consider regulation.

Looking Ahead

As you move into native tokens and ERC‑20s next, keep this lens: token ownership is a coordination primitive. Good designs clearly define what is owned (rights), how value accrues (mechanics), and how ownership changes hands (standards and controls). With those pillars, tokens become reliable building blocks for open, interoperable economies.

Is this guide helpful?